The overwhelming conclusion from the research involved in writing Your Life Your Planet was twofold. We cannot consume our way out of an environmental crisis and food is our biggest challenge. This article explains why and how we address both problems.

The aim of this research was to compare the average Australian household to the rest of the world and to the consumption levels needed to avoid climate and environmental disaster. The result was three personal targets, the carbon target, the water target and the wellbeing index. They are shown in this article, explained in detail in the book and will be summarized Real Soon Now in an article coming to you.

What became apparent, though, from writing the book, is that we cannot achieve our personal targets while living a normal daily life in this world, and that we have no control over activities like war, industrial food production, and our electronic infrastructure. We can limit our involvement and support for these things, we can publicly oppose them and work toward building alternatives, but we cannot radically change them by altering our consumption habits.

So, this article is not about the actual targets and the details of the research, this article is about the implications of the findings.

When I say that we cannot consume our way out of a crisis that does not mean that we should not think about what we consume, what it does mean is that we should not whip ourselves with guilt when we recognize that there are limits to the impact that our consumption choices have.

I worked in the local library while I was writing the book because it was hot and I did not have an air conditioner at home. I ended up driving my car to the library because it was so hot that when I rode my bike I arrived at the library dripping with sweat and then froze in the air conditioning and probably made life very unpleasant for other library users because I smelled like an old billy-goat. The irony of driving a petrol-powered car to a library to enjoy air-conditioning while writing about reducing your environmental impact was not lost on me so I included it in the preface of the book.

The point is that we consume for convenience and comfort, which are natural desires, and that there is no point promoting austerity as a long-term solution to the madness of a consumption crazed world.

The hub of production

As a result, my focus shifted to finding the alternatives. I was happy as a child in the mid-twentieth century, living with a fraction of the consumer goods that we have now, in a world without plastic, electronics, or sewers. That does not mean that I want to deprive my grandchildren of the advantages these things offer, what it does mean is that I want to make them aware of the choices they make about comfort.

We don’t need single use plastics, bottled drinks, or disposable anything. There might be occasions when they are useful, but they are not necessary or generally desirable.

Public transport might be slower than driving, but we can read, socialize, and engage with the world as we travel instead of isolating ourselves in our entertainment bubble.

We can make music with other people, share food, design clothes, walk the neighbourhood and improve our physical and mental health, build community and learn useful skills instead of consuming passive entertainment, processed food, and fast fashion.

Because we are driven by convenience and comfort, finding ways to achieve multiple things at the same time is one way to reduce consumption. Read, chat and build your dreams as you travel. Eat healthy food, exercise your body and your mind, and repair well made goods as you socialize with your family, friends, and neighbours.

By sharing things, we create we convert our homes from nodes of consumption into hubs of production. This phrase, delivered to me by Cat Green at the launch of a book called Fair Food, became the motto for Your Life Your Planet.

The challenge of food

Given that I was focused on carbon, water and wellness targets as I did the original research for the book, I ended up with a detailed accounting of the carbon emissions and water usage of the average Australian household. I quickly realised that the average household is a very artificial concept. Families are very different than people who live alone. Tasmanians heat their houses with wood, Victorians with gas, and Queenslanders by opening the window. Despite this, I persisted with the calculation as a useful starting point, figuring that once we had the methodology in place we could easily adjust the calculation based on the location, number of people in the household, mode of transport, etc.

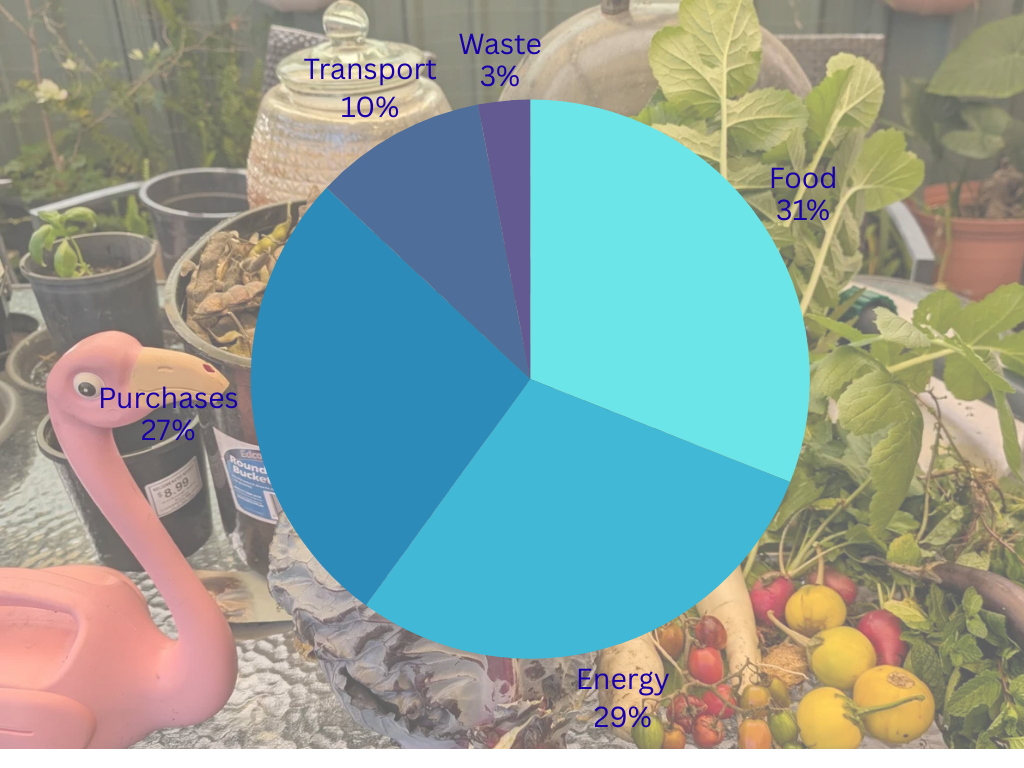

I was shocked to find that 31% of average household emissions come from the food we consume. That is higher than the 29% due to the energy we use, or the 27% from the stuff we buy. Those three categories account for 87% of our emissions, leaving 10% for transport and 3% produced by our waste. Solar panels and energy efficiency are rapidly reducing the impact of our energy. When I first did these calculations in 2005 energy consumption produced more than 35% of our emissions and food less than 30%. The difference is almost solely due to the introduction of renewable electricity.

We focus so much on energy and transport while barely discussing the impact of food. Energy and transport are relatively simple processes. Energy production is pure physics, we convert one form of energy into another. Traditionally we created heat, and used that to generate motion, and converted that motion into electricity. Hydro electricity was the exception, converting gravity into the movement of water to spin a turbine. Travel involves a lot of mechanical engineering, but the internal combustion engine is essentially a method of capturing the explosive energy of putting a spark into a mixture of fuel and air and converting that into movement. Electrifying the transport fleet allows us to move around on electricity captured from sunlight and wind power.

Food is infinitely more complicated. For a start it is a biological process. It combines energy from the sun, water and nutrients to drive the biochemical processes that capture that energy to build the complex carbohydrates on which the entire food web depends. This involves the carbon, water and nitrogen cycles, soil health, biodiversity and other interactions with nature such as pests, weather, and decay. And that is just the process of producing food in the first place. We then need to consider the processing of food, distribution and storage, and the retail, delivery and consumption.

Energy and transport are analogous to the blood supply in the human body, the nervous system, or the skeleton-muscular framework that enables us to move about. Food involves the social interaction of a whole network of different animals all with their own internal complex of venous, nervous and skeleton-muscular systems.

We only eat a small amount of the plants and animals that we breed and grow as food. We waste food on the farm, during processing, distribution, retail and at home. Not only do we throw away the energy and resources that went into the food at each of those stages, but that waste produces its own emissions and has an impact on other global systems. Food is complex.

It seems amazing that we look at the towering cities around us, brightly lit, humming with energy, buzzing with movement but the stuff that we eat still uses as many resources as the built environment. One of the best demonstrations of the amount of energy it takes to power the human body is the film made by students in Stockholm showing an Olympic cyclist powering a toaster to toast a slice of bread. We all eat more energy than we require every day. That is not a judgmental statement, it is a scientific fact: if we did not, we would die. It is little wonder, then, that the industrial agricultural complex has produced around five times the emissions of the industrial military complex in recent decades.

The role of industry in this statement is important. There were large cities of hundreds of thousands of people in the past that did not rely on agriculture to feed them. They fed themselves internally, growing food communally in common spaces and keeping birds and animals on roof tops and balconies, allowing milking cows to wander the streets. Our addiction to convenience and comfort has created the complex system that is the current food supply and our preference for the tastiest sweetest part of the plant and animal has created the vast fields of waste that results.

By applying the simple formula of converting our homes from nodes of consumption into hubs of production we can start the process of reversing this ridiculous, wasteful, poisonous food system into an everyday experience of sharing the simple joys of producing, preparing and eating food together. This is the fundamental premise of Your Plant, Your Planet and Your Plate, Your Planet the twin spin-offs from the book.