The tyranny of the majority stifles diversity. So do the rampaging trolls.

Community-based regenerative food is grass-roots sustainable materialism. It is hardly a mainstream solution. Governments ignore its capacity to provide resilience because they cannot comprehend the importance of nurturing diversity. The shrill harping of trolls on the rampage make it harder to accommodate diverse opinions.

It’s a sunny Saturday after a wet summer and two dozen neighbours are feasting on the harvest of our community garden. The owners are mostly Anglo and are enjoying garden salad and baked sweet potatoes with their steak, the culturally eclectic tenants are arranging the eggplant and okra curry and tuvar dal (pigeon peas) onto steamed rice. All the vegies have been grown here in our food forest, now two years old and regularly producing everything from strawberries to banana, turmeric to tomatoes and lettuce to native spinach. It’s a feast.

Like any community project, not all is harmony and light:

- One participant believes that offering free food will weaken the gene pool and wants us to charge for lunch.

- Another thinks that eating off plates generates too much work and would restrict lunch to sausages on bread or, if we must eat fancy, at least decree plastic plates and implements.

- The Clive Palmer and Pauline Hanson voters tend to dominate the conversation after a few cooling ales and terrify the teetotal tenants. Freedom to hector, vs freedom from…

We hold it together for the sake of community. After all, we have to live with each other, and this garden is part of our long-term survival plan. Everyone predicts tough times.

Logan is one of Australia’s welfare hot spots, an ALP stronghold where only independents bother to run against them in council elections and the LNP fans the flames of populism to make a dent in Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ hold on the Federal seat.

This feast celebrating our community garden offers a microcosm of the chasm between collectivism and individualism but also provides a small but active example of grassroots sustainable materialism – so eloquently described by David Schlosberg in Green Agenda last November. It offers a small-scale but resilient alternative to the inherent fragility of complex, just-in-time distribution networks of global, corporate agribusiness which was recently exposed by a ‘perfect storm’ of disruption. That disruption triggered a parliamentary inquiry into Food Security.

Australian Food Story

The Australian Parliament House Standing Committee on Agriculture Inquiry into Food Security (the Inquiry) reported in November 2023 after considering 180 submissions over one year of deliberations. The name of the Inquiry’s report is Australian Food Story: Feeding the Nation.

The terms of reference asked the Committee to inquire into strengthening and safeguarding food security, including the examination of:

- national production, consumption and export of food;

- access to key inputs such as fuel, fertiliser and labour;

- supply chain distribution;

- the opportunities and threats of climate change.

I emphasise opportunities because promoting them as having equal weight to the threats is simply an excuse for business as usual.

The background to the inquiry argued that the pandemic and the ‘illegal and immoral’ war in the Ukraine disrupted Australia’s food imports and the inputs – such as fuel, fertilizer, labour, fencing wire, and star pickets – on which our food production depends. The disruptions of CoViD and the Ukraine war are the stated reasons that the recent Food Security Inquiry focused on Australia’s dependence on international trade to feed itself. The ‘perfect storm’ of disruption, though, incorporated other factors. While we export lots of food commodities – grain, meat, dairy, pulses, wine, seafood – we import much of our horticultural produce and processed food. The impact of belligerent sabre-rattling with the world’s largest economy and, hence, our largest trading partner, hurt farmers. And (the opportunities provided by) extreme weather caused lettuce and potato crops to rot on-farm. Who can forget the $12 lettuce and its contemporary news event the AUKUS submarine deal?

I provided a copy of my research into the viability of sustainable food systems in SEQ as one of 180 submissions and then analysed the submissions using the same methodology, examining the sources of cognitive dissonance to identify the intersection of vested interests.

The Inquiry was an opportunity to rethink the relationship between food and wellness, agriculture and the environment, the sustainable wisdom of First Nations people and the short-sighted extractive industry of agri-business. Instead, the report, and the Government response to it, echo Chalmers’ wellness budget; a neo-liberal blueprint with a conscience. The Inquiry’s report, the government’s response and the budget all focus on economic growth, proposing (at best) to decouple ‘growth’ from environmental harm. The result is a scattergun approach, offsetting the amplification of ‘business as usual’ with a handful of headline responses to address the most obvious, contemporary symptoms while completely avoiding the root cause. We know the risks but will back increased production, increased trade, and increased industrialisation of food production because it makes money and because that’s what we know how to do.

Around two thirds of the submissions are from producers (grain growers, meat producers, fishing, aquaculture, horticulture) and the supply chain (processors, wholesalers, retailers, chemical companies, pipe manufacturers). Most of these follow a standard formula: fund our expansion, remove regulations that restrict us, regulate our competitors (especially international ones), and regulate the supply chains that exploit us (especially the supermarkets and the supply chains they dominate). My somewhat cynical summary is “Get out of our way, put a protective fence around us and help us sell our product and we’ll feed Australia and earn some big export dollars as well.”

Another sixth offer techno solutions to make business better than usual. These come from investors, inventors, and Universities and most of them are promoting their own ‘future of food’ solutions. Combined, these 150 submissions assume that food security is about the availability of food, “Grow more food, feed more people”.

But there are three other definitions of food security used by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO): food access (equity or justice), food utilisation (quality or nutrition) and food stability. Many of the remaining 30 address start with these definitions. Government agencies, the health sector, concerned individuals, and scholars doing social research considered food as a fundamental input into wellness. They pointed out that food can be considered as preventative medicine and, so, implementing good food policy could significantly reduce the financial burden that the existing health system places on the public purse. Many of them called for a Ministry of Food, putting food rather than economic outcomes at the centre of the discussion. In the government response this has morphed into an assistant minister focused on food security, as defined by the Inquiry.

Those submissions generally identify the cost of specific dietary diseases or socio-economic conditions and so look beyond the “feed more people” paradigm, but do not examine why existing food systems lead to poor nutritional and equity outcomes. That leads us to the elephant in the room, mentioned only by a dozen submissions, which is the impact on the environment and the role in plays in underpinning food production.

Only seven submissions mention agro-ecology, one of them in a defence of glyphosate. The Australian Food Story defines Agro-ecology as “perhaps the ultimate response to sustainability and climate change in the agriculture sector”. This does not appear to be a compliment or, at least, an indication of its importance because it is promptly ignored and does not appear once in the government’s response.

If it has occurred to the members of the Standing Committee on Agriculture that there is nothing to eat on a dead planet, they have chosen not to present that framing to government.

The future is already here, but it’s unevenly distributed

It is probably more accurate to assume that politicians in general, and the Inquiry in particular start from the position that human ingenuity will extract us from the existential threats of climate chaos, bio-diversity loss, ocean acidification, falling water tables, dysfunctional nutrient cycles, forever chemicals and the impact of the disruptions these cause on the fabric of society.

Personally, I do not believe that technology can shoulder the compound effect of population growth and its demand for an increase in personal affluence. When I put this to Professor Ross Garnaut in an interview on his recipe for decoupling the economy from environmental harm, Reset, in 2022, he expertly reiterated the litany of solutions that will see us escape the planetary boundaries that restrict economic growth.

He is in good company. George Monbiot and the rewilding brigade see an opportunity to radically shift the production of food away from industrially harming animals toward growing lab meat. Tim Flannery discussing the history and future of Europe points out that we are already on that trajectory, wild wolves and bears have appeared in Europe thanks to this rewilding. High tech food futures range across the sector. Robot fruit pickers, cheap enough to prevent farmers bulldozing the second crop of capsicums into the ground; gene-sliced bananas that offer sufficient diversity to ameliorate the fears that 47% of the world’s banana crop is a clone of Lord Cavendish’s greenhouse plant and highly vulnerable to disease; micro watering and nutrient delivery to individual seeds, reducing wastage of nutrients; bio-synthesis of everything from 3d printed wagyu steaks to a modern Soylent Green in stainless steel vats funded by the Queensland Government in Mackay to make better use of sugar cane. The Future is already here …

In addition to new processes, the circular economists see an opportunity to reduce the extraction of new resources, increase efficiency and creatively manage existing imbalances in the system to offset one problem against the other. Food waste charities consider themselves circular and have been awarded hundreds of millions by government to nourish the less fortunate. The supermarkets reject tonnes of food grown by farmers on the basis of shape, condition or “unsuitability” and deny that they are simply discarding excess product to maintain their margin. To prevent that “rejected” food from becoming “waste” and producing methane or costing them money, the supermarkets generously donate it to charity, gaining tax deductions for the value of the food that they have not paid for, or had to pay waste processors to handle. The charity, staffed by volunteers and funded by government to address issues of food equity, repackages that food for distribution through front line services who deliver it to the needy. The circular economy reducing waste while externalising its costs and receiving funding from the tax payer. The farmers, of course, pay the price.

Big Money is not always so cynical though.

Regenerative beef growers also win big in the Inquiry’s report. The recommendations 23 through 26 of the Inquiry relate to this sector and call for investment in emissions reduction, natural capital markets, grants for sustainable agriculture and support for states investing in landscape restoration.

As a nature-based solution, regenerative meat growers have a significant advantage of a reduction in the use of technology, thereby minimising infrastructure and its emissions while increasing resilience. This has the triple effect of reducing costs and environmental damage while also reducing reliance on external inputs that make farmers vulnerable to international crises. It is no co-incidence that it is now attracting big money, with the Murdoch family investing heavily in grass-fed beef using regenerative cell-grazing approaches in Montana.

The government has also vowed to fund regional and remote indigenous communities to establish local food solutions and to work with state and local government to protect peri-urban land. Perhaps someone was listening at the Urban Food Roundtable.

Building better policy

Old white men in oil paints stare down from the walls of Queensland Parliament House at the participants in the first Queensland Urban Agriculture Roundtable. It is September 2022. The federal inquiry into food security is still a twinkle in some committee members’ eyes but local government, First Nations representatives, farmers and industry lobbyists join a handful of academics in discussing the challenges of feeding an increasingly urban population.

There are many visions, many stumbling blocks and differing priorities but there is good will and recognition of a common concern for the future. We discuss food deserts in suburban metropolitan areas, remote communities and regional towns surrounded by food production. We discuss the difference between commodities like sorghum or wheat, on one hand, and fresh food or meals, on the other. We discuss the collapse of food processing and manufacturing across the Australian economy, and the collapse of rural populations as corporations have bought up the family farm and replaced farming communities with high tech machinery, remote managers, and local operators. We discuss the role of community farms, food tourism, food justice and the loss of peri-urban farmland. There are a handful of representatives from local government juggling demands for housing, environmental protection and agriculture on the peripheries of metropolitan sprawl.

From a policy management perspective, Urban food presents a typically wicked problem. It is one that I have examined in some detail.

The socialists call us ‘swampies’

Consensus is easy with a broad brush. Sustainable Table’s Regenerating Investment in Food and Farming (RIFF) puts it thus: “Our focus is on the deep transformative work that is underway to reconfigure our food and fibre systems. Actions that not only ‘do less harm’ and operate within planetary limits, but actively regenerate — restoring ecological and social communities, sequestering carbon, reconfiguring right relationships, and renewing soil and water cycles.”

As we get more specific about our solutions, though, the consensus falls apart.

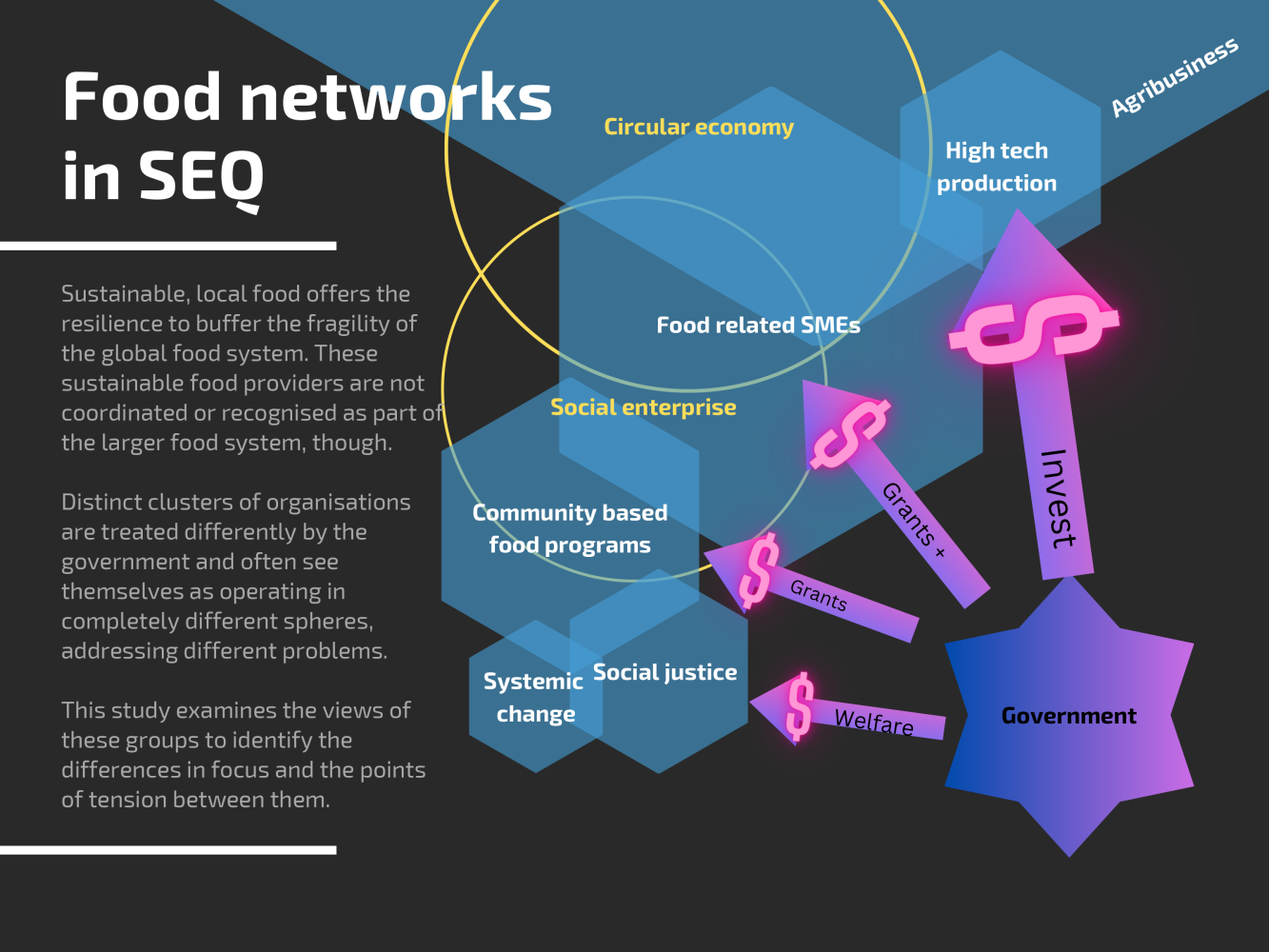

My mapping of the intentions, challenges and responses of food providers attempting to operate sustainably in Southeast Queensland confirms the innate tension between corporate agribusiness and attempts at deep sustainability. It also identifies a rich field of responses to actively regenerate ecological and social communities and so create an alternative future.

Community food hubs across the nation offer a catalyst for coordinating change: Food Connect Brisbane – where I volunteer, Southern Harvest in the ACT, Food Next Door in Mildura, Fleurieu Community Foundation… Some fail, but often that failure is temporary. New members join them, revitalise them, and start from different initial conditions, building on the work of earlier contributors.

The networks of food hubs are growing: Open Food Networks, Tasmanian Produce Collective, Community Hubs Australia. The philanthropists and funding organisations are growing, learning and building capacity: Sustainable Table, Australian Environmental Grantmakers Network, ORICOOP, Farming Together. These funds and organisations are building maps and directories: Regenerative Farming Australia, Local Food Connect, Sustainable Table’s map …

There is a problem, though. My research also revealed significant other tensions that undermine these progressive efforts.

The socialists call the permaculturists, foragers, and community gardeners “swampies”. The food-equity and food-charity sectors consider inner-city urban growers self-indulgent yuppies more worried about the perfect lettuce and the price of real-estate than feeding people. The systemic thinkers study the externalising of costs to farmers and the environment and see the political wing of the movement as fighting last century’s economic battles in the face of an imminent existential crisis.

These are not backroom disputes that take place late at night after an excess of ‘red cordial’. These are active battles on the ground in community spaces. A herb mandala built by semi-retired ‘greenies’ affiliated with a wellness centre in their local village, is brutally dissected by the encroachment of tightly packed rows of well fertilized and watered greens grown by a well-funded food charity, delivering fresh food to other food charities. The epithets each group throws at the other would not be out of place on a nineteenth century sailing ship. Guerilla gardeners are confronted by civic minded home owning environmental activists who see rule-breaking disruption as counter-productive. I get the picture: I had to excise all references to Extinction Rebellion from Your Life Your Planet to get it published.

If we will not go to war over our beliefs, then we face the danger of being subsumed by what is most palatable to the majority. But the first casualty of war is truth and its death is preceded by the symptoms of misunderstanding, misrepresentation and a failure to acknowledge the humanity of the opponent.

Sustainable Table points out that change occurs “at the speed of trust” and that we “can only meet people where we are”. In the context of my research, I read this as meaning that we need to learn to live with the normative dissonance at the core of our communities. We need to accept that the twin forces of the selfish desire to accumulate and grow and the communal impulse to connect and benefit from shared experience often pull in different directions.

In food we trust

I attempt to get people to scrape food scraps into the compost, but the third drink has kicked in and the protests are furious and shrill. I am drowning in a gyre of single-use plastic and deep fat when someone gently asks me to show them through the food forest.

“I recognise a great many plants, but there are also many I have not seen before. I hope that you can introduce me to these strangers.”

As we stroll, we identify maringa, rosella, cassava, brazilian cherry, tulsi, varieties of ginger and turmeric, malabar spinach, madagascar beans, the tuvar dal we have just finished eating. I learn that tulsi should be grown as a holy plant and that what I have is a wild tulsi that escaped cultivation. It is clear that I should learn to care for and respect its sanctity.

This is how the garden is supposed to work. The sharing of culture and knowledge; the integration of food, medicine and spirituality: these are the outcomes of integrated, grass-roots food systems. This is why we build them.

Queering the economy

As a nation, we have signed up to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Climate agreement, and numerous other treaties, but we are incapable of delivering on our promises. We set out to manage the worst excesses of business as usual and spend all our time fighting over the disruption caused by the most timid of changes, without ever getting to the core problems.

Much science and speculative fiction identifies a future dominated by corporations. Yanis Varoufakis focuses on “corporate feudalism” as the defining feature of our age. What is dysfunctional about these futures? I mean the question seriously. If Monbiot and Flannery can seriously support rewilding of the landscape enabled by more efficient food production, why would we not embrace the benefits of a high-tech food future and the slightly Disneyesque view of nature that it enables?

Capitalism is undoubtedly exploitative and extractive, but it is an amorphous adversary that shape-shifts whenever you try to pin it to the target. Feminist social geographer, Gibson-Graham, nailed it with their work on “queering the economy”, A Postcapitalist Politics. Their approach of identifying existing economic practices that are not capitalist in nature (so undervalued in large scale analyses and policy responses) and coordinating these relational exchanges to build community scale responses, goes to the heart of grassroots sustainable materialism.

The practical actions required to achieve this are difficult. While land is a commodity, only corporations can afford to invest in land to grow food. While capital is impatient and investors determine the required return on investment food systems will continue to evolve to cut costs and deliver volume. While First Nations farmers are expected to compete on an “even playing field” with farmers who are subsidised to use European farming practices in the face of a hostile climate, we cannot learn from the accumulated wisdom of 600 centuries of sustainable agriculture. While the supermarket duopoly and the car-based shopping mall are supported by infrastructure that favours the separation of production and consumption we will not learn to convert our home from nodes of consumption to hubs of production.

Bottom up and top down

These are systemic challenges that require careful nurturing of grass roots organisations and their consolidation into hubs and networks and ecosystems of alternative economies, economies that are relational rather than transactional, that measure contribution and outcome in non-monetary units. In short, this requires imagination from government that is entirely lacking in the response to the Inquiry into Food Security.

Governments need to embrace both the notions of decoupling economic growth from environmental harm and of nurturing the grass roots materialism that offers a buffer to the fragility of industrial efficiency, if not an alternative. They need to listen to the systemic thinkers who have identified the problems implicit in an extractive and exploitative market economy and they need to support the development of infrastructure that reverses the alienation and depletion of humanity that the market economy causes.

That does not mean turning our back on the market, it means recognising that there is not an optimal solution, so there must be pluralist solution. The devil is not just in the detail, it is in the dissonance that occurs at the intersection of belief systems. The progressive movement is not fragmented because of a lack of passion, or common sense, it is fractured because we are all passionate about different aspects of complex interdependent systems.

We are active, engaged citizens. We understand the systemic nature of the problem and we understand that scale of the challenge, the complex nature of the systems we are trying to change, and the normative dissonance involved in attempting to reverse an extractive and exploitative system that has evolved for no reason other than the human desire for comfort and convenience with a good measure of greed thrown in.

We do not need to look beyond our own back yard, the community compost at the end of the street, or the committee organising the spring street fair to know how hard it is to overcome that normative dissonance. We need to engage in community, to nurture the systems that will connect our communities together, that will provide the diversity and the resilience to compete with the efficient, profitable but oh so fragile systems that exploit us. And most of all, we need to recognise that this is actually hard work.

#communitygardens #regenerativefood #foodsecurity #sustainablematerialism #dialectic #wickedproblems

References

Inquiry https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Agriculture/FoodsecurityinAustrali

Report Australian Food Story: Feeding the Nation and Beyond

Author’s initial analysis of submissions

https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=34221367-8589-40fe-a628-07b47ccb435f&subId=744530

Regenerating Investment in Food and Farming

https://www.sustainabletable.org.au/learn/regenerating-investment-in-food-and-farming

Geoff locks Professor Garnaut into the Cage

https://ecoradio.net/ross-garnaut-defends-reset-in-the-cage/